The impetus for teaching myself Python and native AWS services was an idea that I had one weekend: One of the products that I sell as part of my job at VMware is VMware Cloud Disaster Recovery (VCDR), which allows organizations to store a backup copy of their VMware vSphere virtual machines in AWS and quickly recover them into VMware Cloud on AWS (VMC) in the event of a disaster. VCDR is a great product, but many of the organizations that I talk to are already using other data protection products to achieve something similar. What if there was a semi-automated way to leverage the existing data protection product that you’re already using and combine it with some scripting and native AWS services to perform a disaster recovery failover of your workloads into VMC?

On top of that, what if there was a way to leverage existing data sources on the Internet to determine if a disaster recovery failover event was needed?

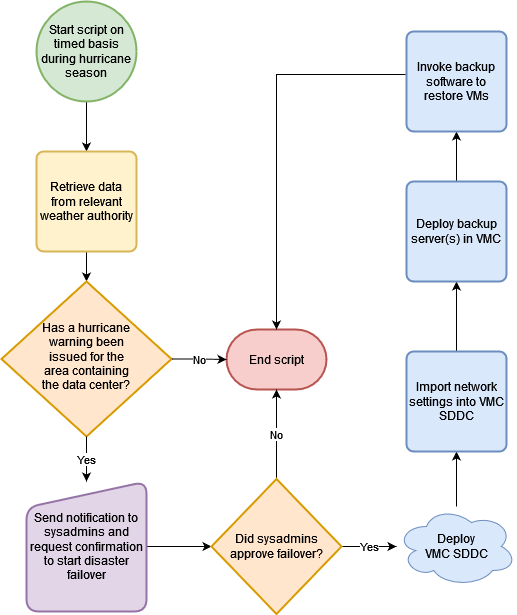

My idea is to combine the power of AWS Lambda with specially-crafted Python scripts to check the RSS feeds of weather agencies to determine if a hurricane warning has been issued for the geographic area containing your on-premises data center. If a warning has been issued, send a notification to the appropriate group of system administrators or I.T. personnel at your organization and ask for their confirmation to perform a failover. If they approve the failover, execute a series of AWS Lambda scripts to create a new VMC Software Defined Data Center (SDDC) in AWS, import your network and firewall settings, deploy appropriate backup servers in VMC, and invoke the backup software to restore your virtual machines.

Throughout this blog post and this disaster recovery project I’ll be using the term “hurricane”, but I realize that these storms are called “typhoons” or “tropical cyclones” in other parts of the world. When I use the word “hurricane” you can assume that I’m also referring to typhoons and tropical cyclones too.

The following flowchart diagram illustrates the high-level processes:

In order for this to work, certain prerequisites need to be met:

- The on-premises workloads need to be VMware vSphere virtual machines. Alternatively, the data protection software package should be able to convert the workloads at the time of restore into VMware vSphere virtual machines (such as converting the backups of a physical server into a VMware vSphere virtual machine, also known as “P2V”). This workflow doesn’t handle workloads which cannot run on top of VMware vSphere, such as SPARC Solaris servers or IBM AIX servers.

- All of the workloads which need to be recovered in the event of a hurricane must be protected (backed up) by a data protection product.

- The backup images created by the data protection product must be stored offsite in the cloud. Even better would be for these images to be stored in an AWS storage service such as Amazon S3.

- The workloads are capable of running in VMC. In other words, the workloads don’t have technical requirements (such as physical hardware device requirements like USB keys or Graphic Processing Units (GPUs)) or compliance/regulatory requirements (such as data sovereignty rules) which would prevent the workloads from running in VMC.

- The on-premises data center is in a country where hurricanes occur, but the country’s government or weather agencies don’t issue hurricane warnings in a format which could be retrieved and processed by a Python script.

Some questions I’ve received so far from my peers regarding this project:

Since you sell VCDR, why not just use VCDR to do the recovery?

Yes, you could definitely use VCDR to do a recovery of your vSphere workloads into VMC in the event of a hurricane. But at the moment (as of December 2021) VCDR does not have a REST API. All disaster recovery failovers into VMC with VCDR must be initiated manually via VCDR’s web-based GUI. It’s difficult to automate a web-based GUI interaction via Python scripts. If VCDR supports a REST API in the future, I will modify the steps and scripts in this project to allow it to leverage those functions too.

Why hurricanes? Why not some other disaster event such as an earthquake, volcanic eruption, tornado, or tsunami?

Undoubtedly those are definitely natural disasters which can disrupt or destroy a data center. I chose hurricanes because they usually form over the ocean and provide enough advanced warning before they make landfall. This gives you enough time to effectively create a VMC SDDC from scratch, deploy your backup software into the SDDC, and restore your workloads. This process could take several hours, depending on how many workloads you have and how large they are. Events such as tornadoes, earthquakes, tsunamis, or volcanic eruptions tend to happen with little or no advanced warning, making it difficult to perform an effective disaster recovery failover in a timely manner.

Additionally, hurricanes affect a large area and cause widespread devastation. It can take weeks or months to recover from a powerful hurricane or a super-typhoon, which makes recovering your workloads into the cloud more important to ensure that your organization’s I.T. assets are up and running in a stable region.

Why use AWS Lambda to run these scripts? Why not run them on an on-premises server or in an Amazon EC2 instance?

My goal with this project is to have the scripts running in a separate region from the on-premises data center. Running the scripts in the on-premises data center would certainly work, but they would also be vulnerable to the same hurricane that could potentially destroy the on-premises data center.

I’m choosing AWS Lambda to run these scripts for a few reasons:

- AWS Lambda scripts are incredibly inexpensive. I envision that most organizations could implement and run these scripts at zero cost (until a disaster failover occurs) because AWS Lambda allows one million Lambda function invocations per month as part of the AWS Free Tier.

- Amazon EC2 instances could certainly run these scripts but they would incur a cost. Even the smallest t2.micro EC2 instance and the associated EBS volume is not free. Additionally, the EC2 instance would contain a Linux or Windows operating system which would need to be maintained and periodically patched to ensure it remained stable, secure, and supported. None of those concerns exist with AWS Lambda functions.

Why perform the disaster recovery failover into VMC? Why not perform it into native AWS services such as Amazon EC2?

During a disaster situation such as a hurricane, the last thing most I.T. people want to deal with is trying to learn a new platform or a new set of tools and processes for controlling, monitoring, and managing their servers and workloads. By performing the disaster recovery failover into VMC, it keeps your workloads in a consistent format (VMware vSphere virtual machines) and it allows your I.T. staff to use familiar tools and processes such as the vCenter Server UI to ensure the workloads are operating correctly.

Performing a disaster recovery failover into native AWS services such as Amazon EC2 is certainly an option, and there are many products on the market which do this very thing. But again, these products and processes involve converting your vSphere workloads into a different format — Amazon Machine Images (AMIs) — and running them on top of a different hypervisor (Amazon Nitro) with a different set of networking and security controls than your organization likely has in its on-premises data center. This adds a level of complexity and stress to an already difficult and stressful situation.

Additionally, most organizations would want to bring their workloads back to their on-premises data center after the disaster has been resolved. If the workloads were converted from VMware vSphere virtual machines into Amazon EC2 instances during the disaster failover, they would need to be converted a second time from Amazon EC2 instances into VMware vSphere virtual machines. This increases the time, complexity, and risk involved in moving the workloads back to the on-premises data center.

If this project interests you, feel free to follow along as I document the process of creating the components and integrating them together. Future posts regarding this project will have the tag “Hurricane DR”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.